Should craft breweries be vilified for selling out to established players? Pete Brown thinks not.

It’s a peculiarly British trait that as soon as we see anything successful, we start to predict its demise. Even if it’s something we really love, we have a grim satisfaction when we can say: “I told you so.” To that end, some people have been saying craft beer is ‘over’ since 2010, even though most people in the UK hadn’t heard of it until around 2013, and its current growth spurt didn’t really get underway until 2016.

So – is craft beer in now, finally, over?

No, of course it isn’t. Despite some commentators fervently wishing it were so, craft beer continues to be the most significant trend across the whole food and drink sector, the biggest thing to happen in beer since Britain traded in traditional ale for trendy lager in the 1970s and 1980s. Like lager in 1976, craft beer has only just begun to make its impact felt.

But, like any product in any market in the whole history of commerce, craft beer is changing – both in terms of what it is, and what it means to the people who drink it.

Styles and fashions change all the time, and food and drink have become style and fashion-led. Ten years ago, India Pale Ale was a pissing contest based around who could make the bitterest beer. Now, IPA brewers are striving to eradicate any trace of bitterness. Between these two points, sourness eclipsed bitterness as the ‘alternative’ flavour du jour.

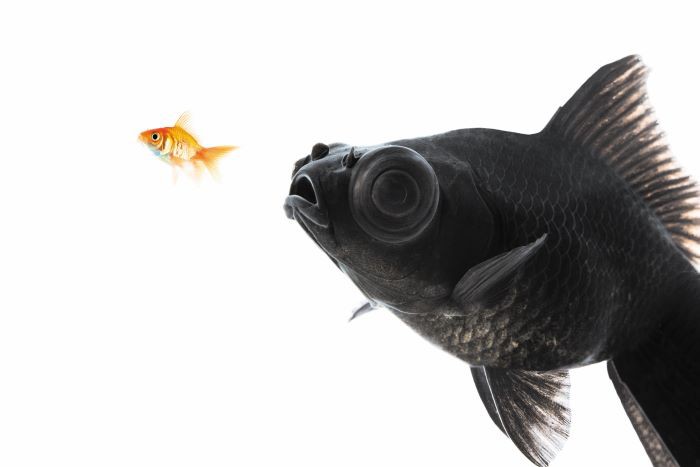

But more than what’s in the glass, the biggest change in craft beer has been the people who put it there. Many of the most beloved names in craft have committed the unthinkable act of selling out to The Man. In the last 12 months, Beavertown, Fourpure, Magic Rock, Dark Star and Fuller’s are just a few of the names to have been acquired in whole or part by the global brewers some of them once railed against.

If you’re someone who approaches craft beer with any degree of rationality, you have to ask what the problem is with start-up firms selling to established players. It happens in every single market. If you start your own business without knowing what your exit strategy is, it’s a little naïve.

As any market matures, it consolidates. Beer is a low-margin product that requires high capital investment. If you want to stay small and make a comfortable living, the only ways of doing so are to be independently wealthy, or to be one of those rare geniuses who can charge a massive premium for the beers you bestow upon the world.

For everyone else, across the entire history of commercial brewing, the only ways to do it are to acquire significant volume, or to sell out to someone who can. “Rich beyond the dreams of avarice” entered the popular vernacular long ago, but it began as a comment by Samuel Johnson about the sale of Henry Thrale’s Southwark brewery to the man who would go on to give his name to Barclay’s bank.

Beer is a commercial product. If someone has given up a well-paid job, remortgaged their house and worked 80 hours a week without paying themselves for several years, and then accepted a sum of money far in excess of the usual financial multipliers that means they never have to work again, who has the right to tell them they are not allowed to do so? Certainly not the keyboard warrior sitting at their desk in a job that pays them a generous monthly salary, tapping away at their smart phone.

The issue is that, to a lot of its adherents, craft beer is more than just a drink – it’s an idea, a position, a set of values. It’s no coincidence that craft beer took off in the UK just after the financial crash of 2008. To many of its fans, craft beer is as much about sticking up two fingers to a monotone world of corporate sludge as it is appreciating the nuances that separate Galaxy hops from Mosaic.

To them, the fundamental question is: if a craft brewer gets bought by a big company, is it still craft?

If you’re feeling snarky, this question can get quite philosophical. At what point exactly does a craft beer stop being craft? If you buy a craft beer on Friday and the brewery gets bought on Monday, is the beer in your fridge still craft or not? Should we draw the line on whether the beer was brewed before the deal was announced, when the contract was signed, or when the discussions with the big guys first started?

From a rational point of view, craft beer is all about the integrity of the product. Either the beer was made to a certain standard with certain ingredients, to hit a certain flavour profile, or it wasn’t. True, big brewers have a lot of form for reducing things to a lowest common denominator – just taste a contemporary, bastardised mainstream lager brand next to the Czech and German pilsners that inspired it.

But should the big guys today be condemned before they’ve even had a chance to touch anything A significant number of commentators within the bubble of craft beer debate believe they should. Rival craft breweries, independent bottle shops, and some very vocal drinkers routinely drop previously adored beers the second their ownership change is announced.

But how meaningful is this discourse that takes place inside the craft beer bubble? The beers that are being bought out and gaining traction with supermarkets and mainstream bars are now targeting drinkers who were previously happy drinking the products of big brewers, or never thought about ownership. Do you know or care who owns the vineyard where your Malbec was made, or your bourbon distilled?

Probably not. But the passion of these fans is part of the value of craft beer. It can’t be replicated in a marketing brainstorm, and there is a risk that takeovers and buyouts dilute its power. Each case must be examined on its own merits.

I believe the Heinekens, Lions and Asahis of the world are buying craft breweries with the sincere intention of not ruining what they’ve paid over the odds for. They know they can’t grow these brands themselves, so they’re forking out on golden geese.

Sure, craft beer has lost its innocence and purity. But like it or not, that’s what happens when you grow up.