With its chequered history across two countries vying to claim the spirit as their own, pisco is a category that is alluring in both background and taste, says Laura Foster.

In this edition of 'Exploring' dear readers, we’re examining pisco, the drink of a thousand puns. Claimed as the national spirit of both Peru and Chile, pisco is a grape brandy. There are some clear differences in the product coming from either country, however.

“In Peru, pisco is something very specific,” explains Tom Bartram, the north & midlands sales manager for Speciality Brands, which represents Barsol pisco. “It’s an unaged brandy distilled from fresh grape musts. It’s always a clear spirit. It’s never aged in casks at all by Peruvian law. It is made in a single distillation using copper pot still, distilling to bottle strength, which has to be between 38% and 48% abv. And it’s the absolute aromatic essence of the grapes it’s distilled from.’

There are eight grape varieties approved for use in Peru, with Quebranta being the most commonly used. There are three categorisations for Peruvian pisco: puro, where it is made with a single grape variety; acholado, which is a blended grape expression; and mosto verde, which is distilled from partially fermented must. “Either of [puro or acholado] can be mosto verde,” says Bartram. “You do mostly see puro mosto verdes, but you also see a few acholados.”

In Chile, meanwhile, things are a bit more relaxed. “Chilean Pisco can be distilled more than once and can be aged in wooden barrels – typically French oak or rauli, a Chilean native tree,” says Gustavo Arancibia, the ‘gerente comercial’ for ABA Pisquera. “That changes the colour to gold or amber and adds the taste of the barrels in which they are aged. Water may be added to lower the proof as well, which must be between 30% and 50% abv – it’s 40% in our case.”

There are 13 approved grape varieties in Chile, with Muscat being the most popular to use. Both copper pot and column stills can be used for distillation.

The differences in pisco between the two countries is a result of their historical fortunes. “In the early days after independence, Chile was a very successful country. Quite a lot more European migration dominated in Chile, it was quite a forward-looking country to what was going on in the rest of the world,” explains Bartram. “Peru is a very traditional country. It's a big mix of different cultures, but it’s been a little bit more locked in its traditions. It wasn’t as successful in the early days of independence.’

Peruvian land reforms courtesy of a dictator called Juan Velasco Alvarado meant that land was handed to people who didn’t know how to tend the plantings, while in the ’80s and ’90s civil war between the government and Shining Path compounded problems. “They almost lost their category, while the Chileans picked up the flak and brought in some modern methods. Meanwhile, Peru put together its denomination in the late ’90s, but made it really traditional,” says Bartram.

Through all of this, Chile and Peru have been at loggerheads as to which country lays claim to the origin of pisco. The result today is that the disagreements between the two countries have spilled into courthouses around the world, as each tries to lay claim to being able to call its own spirit ‘pisco’ in each territory. The UK recognises both Peruvian and Chilean pisco.

However, not everyone is behind this strategy of one-upmanship. “I think this debate helps neither of these countries,” declares Aranciba. “They should be teaming up to improve awareness on Pisco. The opportunity to grow Peruvian and Chilean exports is huge.”

What’s out there?

Tasting through a range of piscos made from different grape varieties, the breadth and variety in flavour is notable, from relatively dry, mineral spirits to blousy, floral numbers.

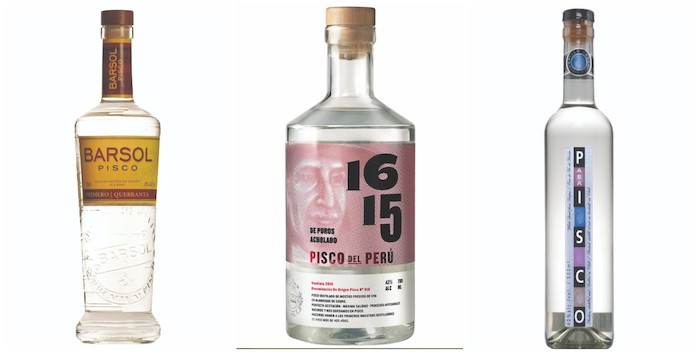

Given the focus on using pisco in cocktails rather than drinking it neat, the suggestions below are for those that are excellent cocktail ingredients, as well as sipping piscos in their own right. Barsol Pisco Quebranta Primero, found at Speciality Brands, is a fabulous introduction, with a lovely rounded nose of overripe honeydew melon, stone fruit and pears. The juicy palate has layers of complexity, with plenty of fruit up front and a white pepper and terracotta dryness in mid-palate, which really dries things out on the finish.

Stocked by Amathus, 1615’s Pisco Acholado from Peru is a blend of Quebranta, Italia, Torontel and Albilla grapes. It has beautiful balance, opening with a creamy character with notes of vanilla, pear and melon, which are overtaken by pencil-shaving spice towards the finish.

Coming from Chile, ABA Pisco – available from Mangrove – is made with Muscat grapes. The nose has an intriguing and pleasing mix of lemon, honeysuckle, seashells and furniture polish, while the palate is rich, round and fruity. Nectarine and tangerine lead on to a significant floral bouquet.

How to drink it

“It’s one of those spirits that people do drink neat on its own – especially the mosto verdes and the aromatic grapes – [in Peru it’s] typically in that tulip-style glass that we associate with grappa,” says Bartram. “But the beauty of pisco is that it mixes really, really well. And I think over 99% of the pisco that we sell probably goes into Pisco Sours or similarstyle cocktails.”

Looking beyond the behemoth that is the Pisco Sour, there are a few other classics: Pisco Punch; Chilcano, which is essentially a Pisco Mule; and El Capitán, which mixes sweet vermouth with pisco.