Professor Shane Eaton’s lab tour takes us to the sous vide. There are few tools better for fast infusion, he says.

Invented in 1799 by American-born British physicist Sir Benjamin Thompson, sous vide was developed in its modern form in the early ’70s by engineer Dr Bruno Goussault, considered the pioneer of the method, who initially applied it to improve the tenderness of roast beef. Compared to traditional cooking, sous vide – which means ‘under vacuum’ – allows for lower temperatures due to the low-pressure environment. The steady application of heat to ingredients in a vacuum- sealed container results in a gentler and more precise preparation that is full of flavour. However, the technique’s benefits aren’t limited to gastronomy, with the modern bartender now using it to quickly impart flavour to liquids.

Sous vide can be used to prepare syrups, infusions and other cocktail ingredients with outstanding results.

Tony Conigliaro is said to have been the first to study the effects of ageing cocktails in a bottle and comparing them through detailed analysis with the same drinks cooked sous vide. Conigliaro discovered that cooking the drinks sous vide will break down the aromatic compounds inside the drink itself, resulting in a better marriage of flavours. The sous vide method can be used for rapidly infusing liquids with ingredients using very low heat for a consistent and delicate result, while avoiding oxidation and evaporation.

The use of sous vide has expanded rapidly since then, but one early pioneer in Italy – where I'm based – is Dario Comini of Nottingham Forest in Milan. He explains there are different variations of sous vide cooking for mixology, but most rely on an immersion circulator, which helps maintain a constant water temperature. First, the liquid is placed in a bag, along with fresh aromas (herbs, flowers, fruit or vegetables), spices or powders, which are cooked inside a water bath at low temperature – from 50°C for delicate materials such as fruit, up to 70°C for harder ingredients such as spices or barks – for an hour or so.

Comini applies this method to make his signature Luxury Box cocktail, for which he combines a litre of rye whiskey, 50g fresh sage, 10g pink pepper and 10g simple syrup in a vacuum-sealed bag. After cooking sous vide for 50 minutes at 57°C, he allows the mixture to cool before filtering into a sterilised bottle, which is conserved in the fridge. To finish the cocktail for the guest, Comini combines 80ml of his sage and pepper infusion with 40ml of Vermouth del Professore, which he serves in a closed wooden box with tobacco smoke emanating from it.

Jerry Thomas in Rome strives to produce a classic and always identical Sazerac, which has a beautiful harmony between its components. Bartenders combine the ingredients (20ml cognac, 40ml rye, 10 ml Gum syrup, 7 dashes Peychaud’s, four dashes Angostura bitters, 15ml water) in a sous vide bag. Then, the contents of the vacuum-sealed bag are cooked for five hours at 55°C. The bag is allowed to cool, with the resulting liquid bottled and stored in the freezer until it’s required for service. To serve the final drink, absinthe is sprayed into a Sazerac glass and the sous vide mixture is poured over it. After adding the essential oils from a lemon, the drink is complete. A perfectly balanced Sazerac that’s always the same.

Model types

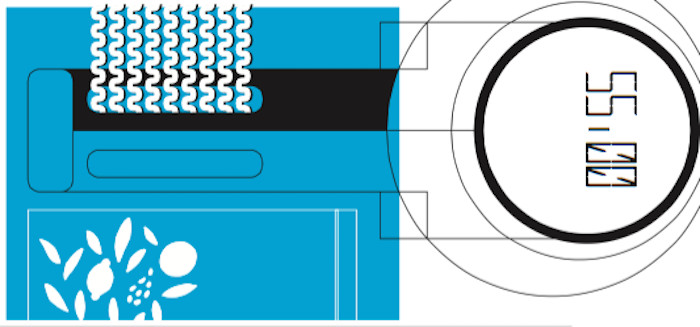

Most bars use £150 immersion circulators such as the Roner or Anova models, designed to heat a water bath and hold it at the desired temperature within 0.1°C. You can also build your own makeshift sous vide with a tightly sealed bag, a simple thermometer and a pot of water. Although this method is economical, it is less consistent due to fluctuations in the temperature of the water bath.

For sealing bags for sous vide, the cheapest way is the water displacement method, where you place the ingredients in a Ziploc bag and seal all but an inch of the bag. By slowly immersing the bag in a container of water, the pressure of the water forces all the air out of the small opening. You can then completely seal the bag before cooking sous vide. For the best results, it is advisable to vacuum seal your bag with an edge-style vacuum sealer or even a high-end, chamber-based vacuum machine. Although the larger chamber-based vacuum machines are costly (£2,000), they can remove more than 99% of the air, bringing the pressure from atmospheric levels (1,013 mbar) down to low vacuum levels of 10 mbar.

Additionally, these commercial vacuum systems can be applied to greatly increase the shelf life of preparations, and even for a second variation of sous vide cooking that Comini exploits to directly boil the liquid and other products at vacuum pressures at room temperature. The reduced boiling point at lower pressure is the same physical principle exploited by the rotovap, as described in my first article.

One example of this method used at Comini’s Nottingham Forest is to infuse rye with rosemary and oregano. He combines a bottle of rye whiskey, 20ml simple syrup, 2 sprigs rosemary, and 30g oregano in a sous vide bag. Then, using a chamber machine, he lowers the pressure to vacuum levels for two minutes before bringing it back to ambient pressure. After filtering, you can conserve this infusion in the fridge, which can make for a great twist on the Manhattan or Boulevardier.

As explained by Existing Condition NY’s Dave Arnold in Liquid Intelligence, chamber sous vide machines are also great for infusing solids with liquids, such as his Cucumber Martini, an edible cocktail of cucumber infused with gin and vermouth. In this case of infusing solids with liquids, it is crucial to keep everything cold (refrigerator temperature) before beginning to avoid boiling your products before reaching the vacuum pressure needed for infusing.

With the low entry point of immersion circulators, sous vide is now invaluable for the modern mixologist. In addition to the advantages of fast infusions and great- tasting preparations, the method has little or no danger in terms of contaminations or safety risks. Naturally, it’s important not to use herbs or flowers that are toxic.

Thankfully, chefs have laid the groundwork for bartenders, and have well- documented safe and tasty ingredients that can enhance the flavour of dishes, and now cocktails.